|

|

PRINT » |

|

|

E-MAIL THIS PAGE » |

|

|

CLOSE THIS WINDOW » |

Vineyard Enology: The Power of Showing Up

VE isn’t dogmatic about how it’s done, and it’s equally comfortable around conventional and Biodynamic producers. What works at one site may fail in another. The focus is on results: flavor depth and complexity, rich active tannin and maximum monomeric color.

“Tannin is almost never the limiting factor in structural and color considerations,” according to Doug Adams of the University of California, Davis, who has studied grape maturation for two decades. “The main issue to address is boosting color development so there is an optimal color-to-tannin ratio.”

As an outgrowth of postmodern winemaking, the discipline is focused on enhancing positives rather than eliminating negatives. If a good structure can be created, then pyrazine aromas can be integrated. Moreover, the very practices that increase color also serve to decrease veg. Pyrazines exist to repel birds, while color is there to attract them. Once the vine switches into seed-maturation mode, the flavors come into balance naturally. Its approach has more in common with Eastern medicine than Western—based on achieving wellness and balance rather than eliminating isolated problems.

The term “living soil” refers to the encouragement of healthy soil ecology through minimal pesticide and herbicide use and encouragement of a healthy cover crop, minimally tilled. It does not necessarily go as far as the extreme and sometimes absurd practices required for organic certification.

The best indicator that all is well is a healthy earthworm population, which leads to an aerated, friable soil to prevent concretion and process organic matter to humus rather than glue formation. Its many advantages include encouraging root depth, canopy control and protection from hot weather spikes by creating soils that provide both water tension and retention, and are thus drier in wet years and wetter in dry years. Living soils enhance wine minerality, increasing palate vibrancy and wine longevity.

Balancing act

Experienced viticulturist Diane Kenworthy of Barricia Vineyards promotes vine balance as the economic meeting place for winemakers and growers. Notwithstanding the acknowledged density of some low-yielding vineyards, the myth that low yields result in greater flavor concentration has little factual support. Drop crop on a vigorous variety with available nutrition and water, and you’re going to get leaves, shading, vegetal aromas, poor color, berry enlargement, diluted flavors and increased rot. Vine balance seeks to optimize color by hanging adequate crop to hold back canopy and obtain flecked sunlight on the fruit.

An important aspect of light exposure is the formation of quercetin, a UV blocker grapes use like suntan oil. Quercetin is formed in response to sun on the fruit early in the season post-bloom, and it has another important use in winemaking. Pigment molecules are not very soluble, and they need to form colloids in order to be extracted into fermenting must. Unfortunately, they are also positively charged and repel each other, and thus cannot form into colloids by themselves, but need to be insulated by similarly shaped, uncharged phenols. Quercetin’s unique flat shape makes it a powerful pigment extraction cofactor.

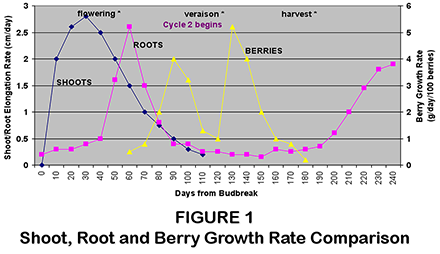

A concerted midseason shift in vine dynamics from vegetal growth to fruit maturation is vital to proper fruit development. The graph above shows the growth phases vines undergo during the season: first shoots, then roots, then berry cellular division (cycle one), followed by post-veraison fruit enlargement and maturation (cycle two), and lastly a root growth spurt post-harvest.

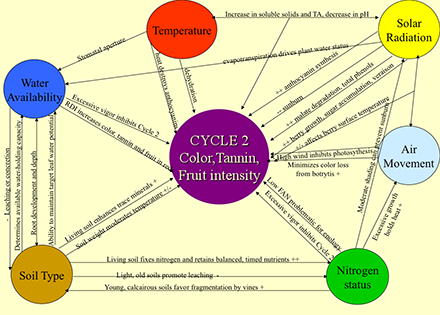

All of the following vineyard conditions must be present in moderation in relation to soil type: water availability, incident light, canopy temperature, air movement and nutrient status. For example, too little sunlight shuts down color and flavor development, but too much causes sunburn. Too little air movement leads to rot, but too much wind results in stomatal closure and shutdown of sugar transport. Each of

these aspects affects all the others. A shot of fertilizer results in more canopy, less light, higher temperatures, less air movement and increased soil water depletion.

In the irrigated vineyards of the American West, the midseason steering wheel for vine balance is irrigation control. Leaf water potential is a preferred tool for gauging water availability, because it makes no assumptions about soil water tension and instead simply asks the vine itself. This technique is equally valuable as a diagnostic tool in unirrigated vineyards in the American East and in Europe.

To measure LWP, a young leaf is taken at solar noon and placed in a pressure chamber with its petiole emerging through a gasket. Gas pressure is then applied until a sap bead appears, duplicating the force with which water is being drawn from the soil. Vines with access to free water read at minus-10 bars or less.

A reading of minus-12 to minus-14 bars at veraison is desirable in promoting the transition to cycle two. This is before tendrils and other canopy indicators will show water stress signs, which set in over minus-14 bars in most cultivars. A reading of minus-17 bars marks the permanent wilt point and is believed to trigger stomatal closure.

Water tension management has been shown to be most effective prior to veraison. Late-season water stress has little beneficial effect on color and flavor development, and it can lead to stressed flavors such as black pepper, and to field oxidation and fruit deterioration.

Marks of maturity

Postmodern principles point to some very specific desired characteristics in red musts. Flavor finesse is achieved through fineness of texture. The smaller the grain size of the colloids that make up the tannin structure, the greater their combined surface area and thus, the greater their power to integrate aromas and their stability over time.

These colloids are aggregates of polymerized tannins formed through the oxidative linking of monomers, much like structures built from Legos (actually a large variety of three-ringed compounds called flavonoids, which build up in grape skins during the season). The winemaker can control this polymerization in the cellar if the tannins arrive in the must as individual Legos rather than the pre-fab polymers, which result from field oxidation.

Oxidative polymerization requires a specific chemical structure on the molecule called a vicinyl diphenol (see February’s column “Creating the Conditions For Graceful Aging”). These daisy chains are terminated when a color monomer (anthocyanin) is added to the chain, because it lacks this feature. Color molecules are the bookends on the polymer; thus, the more color, the softer and more refined the texture. But this only works if the anthocyanin is a free monomer, not already fallen victim to field oxidation.

Berries are formed after bloom and set, then first enlarge to pea size while keeping their green color to camouflage them from birds looking for a meal (cycle one). Once seeds mature, they enter cycle two and color up. The goal of harvest timing is to catch color development when the reactive monomer has hit maximum and before it is lost to polymerization—ripe but not overripe.

An additional consideration is extraction. Since color is extracted from the inside surface of the skin, it is advisable to wait until the gelatinous pectin begins to break down, as indicated by a colored “brush” when the pedicel is pulled away from the berry. In addition, co-pigmentation colloids are destabilized by high alcohol, so high-Brix musts lose much of their color at the end of fermentation.

Stinky is good

A challenging aspect of the postmodern approach is the proclivity of well-extracted, properly ripe musts grown in living soils to produce sulfides. While disconcerting to the novice winemaker, these unpleasant but transitory compounds are a sign of healthy life energy that can be utilized for building good structure, and also indicate aging potential.

The postmodern winemaker’s response to sulfides will vary according to the wine’s intended style and aging curve, a topic for another article. Suffice it here to say that the PM toolkit contains plenty of options for dealing with sulfites, which, unless present in quite gross amounts, are almost never a real problem. Randall Grahm has likened sulfides to acne: If your teenage son doesn’t have pimples, he’s less likely to be happily married when he’s 65. He compared the life energy of young wines and young men with old wines and older men. A well-behaved endocrinology in youth has consequences for libido when it wanes. Similarly, wines that are aromatically closed and/or make a little H2S in youth have more staying power, generally as a consequence of strong reactive tannins, lees, and/or minerality. Personally, I used to worry about wines with H2S; now I worry about wines that don’t have it.

Intolerance of reductive behavior in highly concentrated wines like Cabernet and Syrah has prompted many winemakers to drive the life energy out of their grapes by excessive hang time and field oxidation. While this certainly results in well-behaved young musts, which require little attention and are easily bottled in youth, the practice robs the wines of both longevity and distinctiveness, leaving pruney wines that taste the same and have little shelf life.

It is unfortunate that so many California winemakers have taken this road that we are now typecast in the minds of many of the country’s sommeliers as producers of shallow, short-lived impact wines, and are often not taken as seriously as we once were.

Integrated Brett management

The Integrated Pest Management approach to vineyard ecology encourages beneficial organisms rather than wiping out pests. At one time considered risky and fairly wacky, IPM is now a mainstream viticultural system, but most winemakers have yet to translate its philosophy into the cellar. This bleeding edge practice is known as integrated Brett management (IBM), which similarly promotes wine microbial balance rather than draconian control.

What compels postmodern winemakers to take this apparently risky approach? The same reason there are no sterile filters in dairies. It is th

e realization that the physical properties of a structured food are disrupted by sub-micron filtration. Sterile-filtered milk is no longer milk, and likewise structured wines lose their powers of aromatic integration, flavor depth and soulfulness.

Once the decision is made to eschew sterile filtration, care must be taken to encourage whatever microbiological activity for which the wine is destined. Albert Einstein said, “It is impossible simultaneously to prevent and prepare for war.” Half measures are hard to countenance, because the most dangerous situation is to have only partial stability prior to bottling. The three legs of the IBM stools are nutrient desert, integrative structure and microbial equilibrium.

Creating the conditions for a successful microbial balance starts in the vineyard, with petiolar nitrogen measurements at bloom. The purpose is to determine hotspots where supplemental soil fertilization is required in order to obtain a healthy must that does not require DAP addition to facilitate completion of fermentation. A nutrient desert is created by promoting a healthy and complete fermentation, not only of sugar, but also with regard to the consumption of micronutrients. Brett is a fastidious organism that does not pack the genetic baggage to manufacture many of its essential nutrients. A naturally balanced grape is best, so fermentor additions such as DAP are not necessary. DAP can cause runaway fermentations that achieve sugar dryness without consuming micronutrients. If we feed them Twinkies, they won’t eat their oatmeal.

These aspects of Brett control are an integral part of vineyard enology. Vine balance and proper harvest maturity encourage healthy, complete fermentations, and careful canopy management to promote metabolic manufacture and extraction of dense, well-formed structure can integrate what Brett does occur and render its aromas into positive sensory elements.

An ounce of prevention

Pliny the Elder said, “The best manure is the master’s footsteps.” Kurt Vonnegut said, “90% of life is just showing up.” It’s impossible to overstate the advantages to winemakers of showing up in the vineyard. You are constantly coming across things that you didn’t know that you didn’t know, whether it be a gopher hole, a broken drip head or an insect pressure. It also adds to your spiritual health: There are no atheists in vineyards. From a pure marketing point of view, your genuine knowledge of your wine’s source will inform your presentation of it to customers and enhance your image as the real deal.

Clark Smith is winemaker for WineSmith, founder of the wine technology firm Vinovation. He lectures widely on an ancient yet innovative view of American winemaking. To comment on this column, e-mail edit@winesandvines.com.

|

|

PRINT » |

|

|

E-MAIL THIS ARTICLE » |

|

|

CLOSE THIS WINDOW » |